Producer Insights – with Nick Launay – PART 1

We have just completed a very special interview with none other than producer extraordinaire, Nick Launay. Nick is a veteran of the tape medium, and having had a long standing relationship with both 301 and Steve Smart, he was very kind to offer us his time to share his insights and some hilarious (read: outstanding) stories over a mammoth talk we had with him.

For those that may not know, Nick is an English music Producer, Engineer, and Mixer who has worked with everyone from Arcade Fire, Yeah Yeah Yeahs, Midnight Oil and INXS, to Grinderman, Kate Bush, Phil Collins and Talking Heads – basically, he’s a bonafide legend, and an awfully nice chap to boot.

The focus for our discussion with Nick was to learn about his appreciation of tape – that being, everything from tape splicing, his techniques, the technology, right through to its glorified sound.

To begin the series, he reveals his philosophy on “Analogue vs Digital”.

301: Do you find yourself going back & forth between mediums? For example there are artists like Lenny Kravitz who have gone and bought famous old desks and tape machines, only to dive into large ProTools systems, then later gone back to tape.

Nick: I don’t go back and forth. I would say I go forth only.

301: And what direction is forth?

Nick: Well, I record through vintage equipment all the time, always and only. I capture onto digital through the best A/Ds [analogue to digital convertors] I can find, which are Lavry or Prisms. Those are the two I like the best.

301: Are you going through pre-amps of any sort?

Nick: The studio I use in LA is one my friend owns, but I use all the time. There’s an API desk on its knees over there, and I have a rack of 16x Neve 1081s, so it’s half of a Neve and half an API that totals 48 channels. So I’m going through the best analogue that was ever made. I’m also using vintage tube and ribbon mics.

301: Do you go to tape?

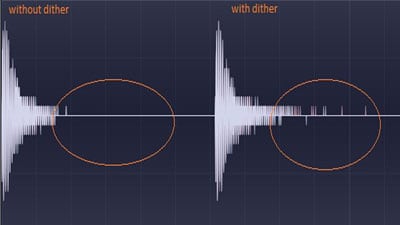

Nick: I don’t print to tape anymore, I used to though. The thing with that is that I’ve worked out other ways of getting that same feeling. And let’s be very clear about one thing… Music primarily is about feeling. That’s what it’s about. The difference between a record that people like or don’t like is the feeling. So the whole romantic thing about analogue tape is, “what feeling is it giving you”? And I think once you recognise that and hone in on that… Is it then about the saturation of the tape? Is it about the distortion of the tape? Is it about the hiss?

It is about all of those things, and those are the names that we can identify, and put onto these things that are important to us. But it’s the feeling that it gives us, versus the incredibly stark nature of digital – which is just this kind of square box instead of it having curves. So I think that there are ways of creating the feeling of analogue tape by cleverly using analogue equipment, and there are also lots of plug-ins that are actually very good.

301: In that case, what is your view of tape emulation plug-ins?

Nick: I think some of them are good. I haven’t used a lot of them. I, again, have different ways of doing things. I think a lot of the great feeling that we used to get from analogue was actually the saturation and distortion. So I use distortion a lot.

301: What about analogue distortion?

Nick: Well, I use Decapitator. Decapitator’s great. I also use Radiator. The thing, I think, the good thing that I have is that I have this very, very strong memory and experience of analogue. So I know what I want to hear and I achieve those sounds and those feelings by using various plug-ins to create it.

301: So when you are using plug-ins, you are referencing your hardware experience?

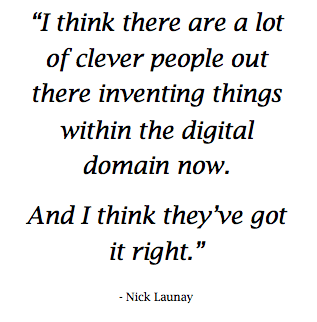

Nick: Yes, in my mind. I’m trying to get back that feeling and I think I managed to achieve it by using various plug-ins. I put things through Amp Farm and Sansamp. The Decapitator is my favourite because you can really vary it a lot. I haven’t used lots of tape simulators like HEAT. I think there are a lot of clever people out there, inventing things within the digital domain now. And I think they’ve got it right. A big round of applause to them because they’ve kind of worked out…. ‘What is it about this analogue thing?’.

For many years, I avoided digital. And then it came – when Pro Tools started being a tool, a very, very sophisticated editing tool, I couldn’t ignore it and I wanted it. So what I ended up doing was recording my backing tracks to tape and my overdubs to Pro Tools. Bear in mind that whenever I work with a band, I always record the whole band together. So let’s say with your average band, you’ve got your bass player, drummer, and two guitar players. So I would do my backing track, i.e. drummer, bass player, and two guitar players all playing at once, playing the song, and then record that onto analogue tape…. that’s 24-track tape. Then I got

it and edited the tape to get the arrangement. Once I was absolutely certain that the arrangement of the song on the tape was brilliant, I would then stripe it with code, and I would then sync it up to Pro Tools and transfer everything into Pro Tools. Then I would continue all my overdubs in Pro Tools. So I’d do all my vocals and vocal comps and guitar takes – and then once I finished, I would sync it up again. When I came to mixing, I would sync up the original 24-track analogue up to Pro Tools and I would mix. So about 50% of what I was mixing was absolutely analogue, analogue, analogue, all original. So the drums, bass, and main guitars were the analogue and all my guitar, keyboards, overdubs, vocal comps, backing vocals, and strings sections would be on digital. I did that for many, many years, probably ten years.

it and edited the tape to get the arrangement. Once I was absolutely certain that the arrangement of the song on the tape was brilliant, I would then stripe it with code, and I would then sync it up to Pro Tools and transfer everything into Pro Tools. Then I would continue all my overdubs in Pro Tools. So I’d do all my vocals and vocal comps and guitar takes – and then once I finished, I would sync it up again. When I came to mixing, I would sync up the original 24-track analogue up to Pro Tools and I would mix. So about 50% of what I was mixing was absolutely analogue, analogue, analogue, all original. So the drums, bass, and main guitars were the analogue and all my guitar, keyboards, overdubs, vocal comps, backing vocals, and strings sections would be on digital. I did that for many, many years, probably ten years.

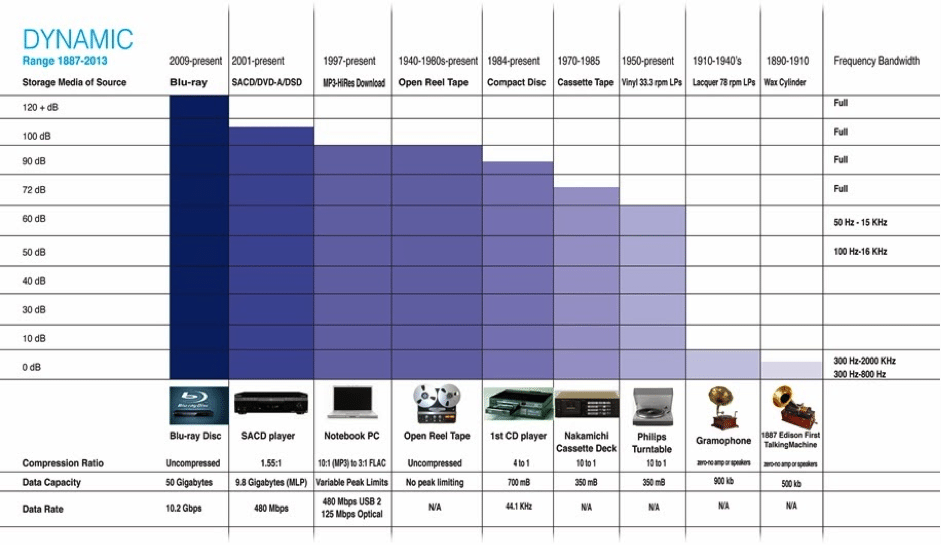

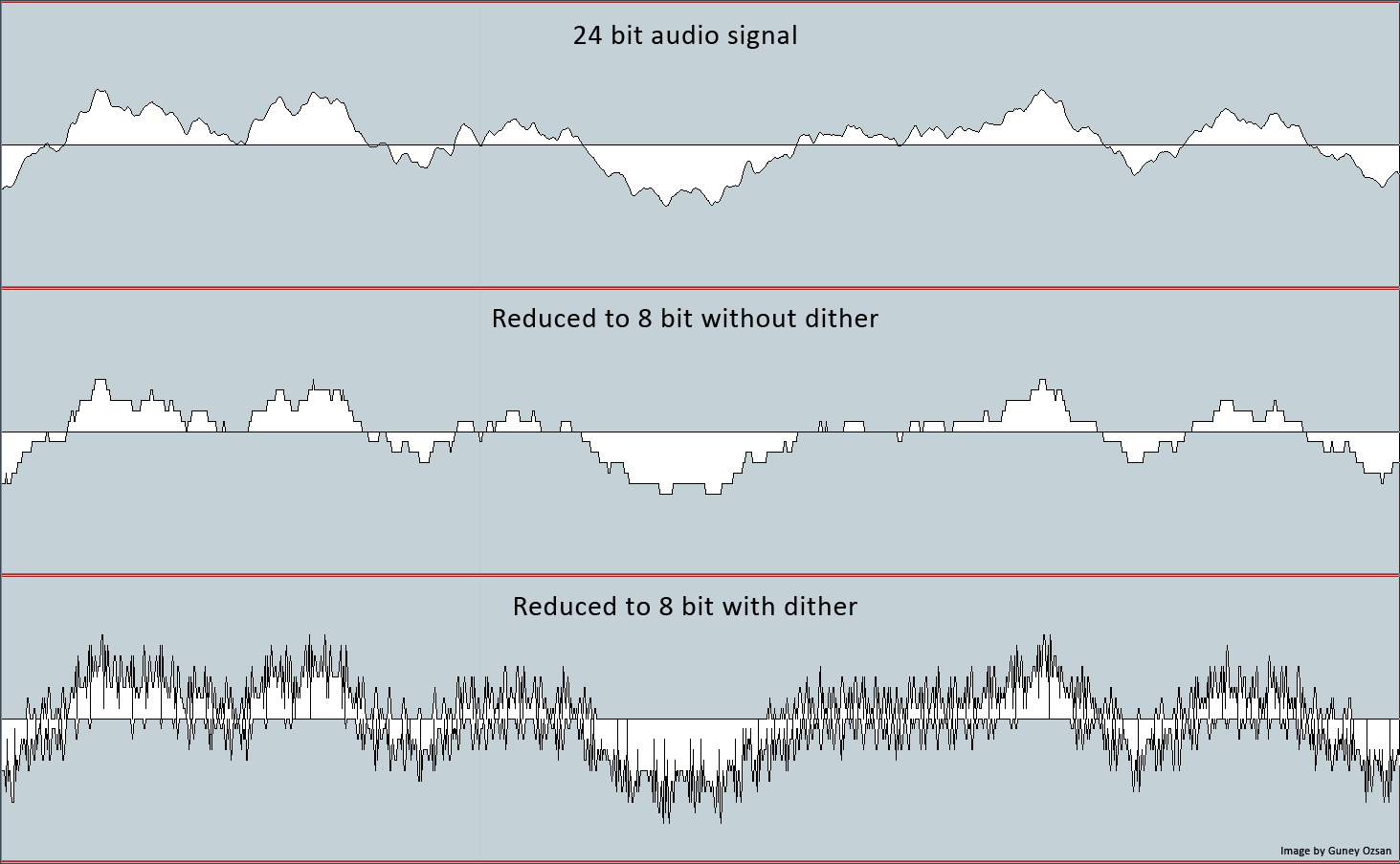

And then about six years ago, I stopped doing that. And the reason for that was when we went to 96kHz. I could hear the difference and it was satisfactory – it was because of two factors.

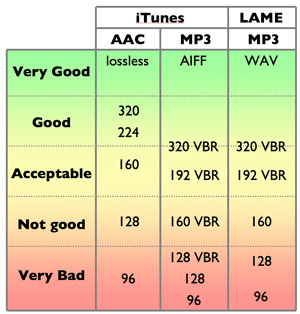

Pro Tools got better sonically. The A/D converters got better. Prisms suddenly existed and also this whole thing of using Pro Tools A/Ds with a library Clock or Big Ben made a huge massive difference. Suddenly, digital didn’t sound quite as bad as it used to. That’s one factor. The other factor which I think you cannot ignore, is that iTunes suddenly became the main way that people are listening to music. In iTunes, most people were listening to MP3s. So in my mind, I just could not justify the little bit of difference that was now the difference between analogue and digital in ‘good digital’.

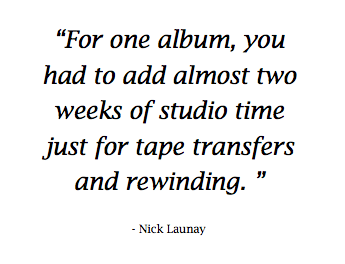

On top of that, there’s also the expense of tape, which now costs about $400 a reel. And the tape machine lining up and realigning, and then the copying time – It was just eating up so much studio time. For one album, you had to add almost two weeks of studio time just for tape transfers and rewinding. The other thing that I started realising, is that young bands that were not used to analogue. Suddenly the singer would be in the mood, they’d do a take, they’d do a great take, and they want to do another one. No. With tape, you have to sit there and wait for the tape to rewind. And then the vibe’s gone. So suddenly I was like, “Hang on. I’m weighing up this tiny bit of romantic-ness of tape versus the reality that most people are gonna listen to an MP3 on iTunes.” … it doesn’t add up.

So that’s when I stopped using analogue recording.

Come back soon for the next part in this series, where Nick discusses tape splicing.

In the meantime, you can also read an interview with Nick in the latest issue of Audio Technology.

it and edited the tape to get the arrangement. Once I was absolutely certain that the arrangement of the song on the tape was brilliant, I would then stripe it with code, and I would then sync it up to Pro Tools and transfer everything into Pro Tools. Then I would continue all my overdubs in Pro Tools. So I’d do all my vocals and vocal comps and guitar takes – and then once I finished, I would sync it up again. When I came to mixing, I would sync up the original 24-track analogue up to Pro Tools and I would mix. So about 50% of what I was mixing was absolutely analogue, analogue, analogue, all original. So the drums, bass, and main guitars were the analogue and all my guitar, keyboards, overdubs, vocal comps, backing vocals, and strings sections would be on digital. I did that for many, many years, probably ten years.

it and edited the tape to get the arrangement. Once I was absolutely certain that the arrangement of the song on the tape was brilliant, I would then stripe it with code, and I would then sync it up to Pro Tools and transfer everything into Pro Tools. Then I would continue all my overdubs in Pro Tools. So I’d do all my vocals and vocal comps and guitar takes – and then once I finished, I would sync it up again. When I came to mixing, I would sync up the original 24-track analogue up to Pro Tools and I would mix. So about 50% of what I was mixing was absolutely analogue, analogue, analogue, all original. So the drums, bass, and main guitars were the analogue and all my guitar, keyboards, overdubs, vocal comps, backing vocals, and strings sections would be on digital. I did that for many, many years, probably ten years.